I am a hardcore Cheesehead – GO PACK GO. Because of that, Vince Lombardi is a hero to me. He’s a legend. He’s one of the greatest coaches of all time. Aside from my fandom, I believe many people will be able to relate with me on the fact that I am also a fan of Lombardi simply because he was a great leader. Leaders like him have paved the way for future generations. To start off this article, I want to break down one of his most famous quotes…

“Practice Doesn’t Make Perfect, Perfect Practice Makes Perfect”

The first thought that came to my mind was, ‘I suppose that seems logical.’

But as I thought deeper, my question is this: if we practice perfectly, where do mistakes occur?

If mistakes don’t happen, where do we learn?

If we don’t learn, where do we grow? How do we improve?

“Perfect” doesn’t seem ideal when it comes to seeking growth; when it comes to seeking improvement.

Now, we don’t know Lombardi’s true intentions, and depending on the context, it could be very valuable. It’s possible that Lombardi was more referring to the intent at which practice is being conducted. Are you truly present in the practice? Are you giving it your full attention?

If you are hitting a 5 iron on the range, are you taking each swing with maximum focus and intent? Or, are you simply swinging away to get through the bucket of balls?

When you read, are you giving the book your maximum intent, or is your brain elsewhere?

Now, Lombardi also said, “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence.” Therefore, it is my personal belief that he was more hinting at the intent to which practice is being completed and the fact that we should always be seeking growth, improvement and betterment. Never be satisfied. Either way, I’ll move on.

The central reason I brought up the quote is that too often I have seen it utilized in a strength and conditioning or team sport setting in regards to human movement and drills.

‘We need perfect shin angles when we accelerate’

‘We need zero valgus while squatting’

‘We need 90 degree joint angles’

‘We need perfect execution’

‘We need perfect reps. If not, we are wasting them’

‘We need 12 yards on our comeback route, not 12.5’

‘We need to eliminate false steps’

Do we actually?

I was an accountant for a year after graduating college. I have a very analytical mind. I like numbers. I like patterns. I like order. I loved when the financial statements agreed with the underlying detail – It was perfect! But guess what, that’s exactly what was wrong with the accountant in me.

I strived for perfection. I strived for cleanliness. I strived for stability. Only to be shoved off my foundation when something went awry or volatility became present.

What does the accountant-strength coach look like?

Perfect squats. Perfect lunges. Perfect shin angles. Load the body in biomechanical advantageous positions. Why put extra stress where it is not needed? Why create a messy environment? Or elicit messy movement?

Because… mess is stress, which creates growth.

Mess is stress.

Awhile back, I published an article discussing adaptation and the importance of stressing the body to elicit adaptations. We were made to adapt, and without a large enough stressor, we can’t.

Article here: https://resistancebandtraining.com/adaptation-and-antifragility/

While stressors come in many different shapes and sizes, it is important that we understand that additional stress is placed on the system when we build a messy environment – or are placed into one.

A sporting environment presents the largest mess (and therefore creates the largest stressors). Intensity is at an all time high. Emotions are running wild. Adrenaline is off the charts. But yet, you need to find the peak of your performance capabilities in these environments.

A large enough stressor will place physical loads on the body, and will further present psychological, mental, and intellectual demands that need to be adapted to. The messier the environment, the larger the struggle, the greater the demands placed on the body, and the more stress will accumulate. However, understand that stressors are good. In fact, they are necessary. To a degree, we need to struggle, we need mess, and we need stress in order to grow.

We need imperfection, in order to strive for perfection.

A Game Changing Research Study

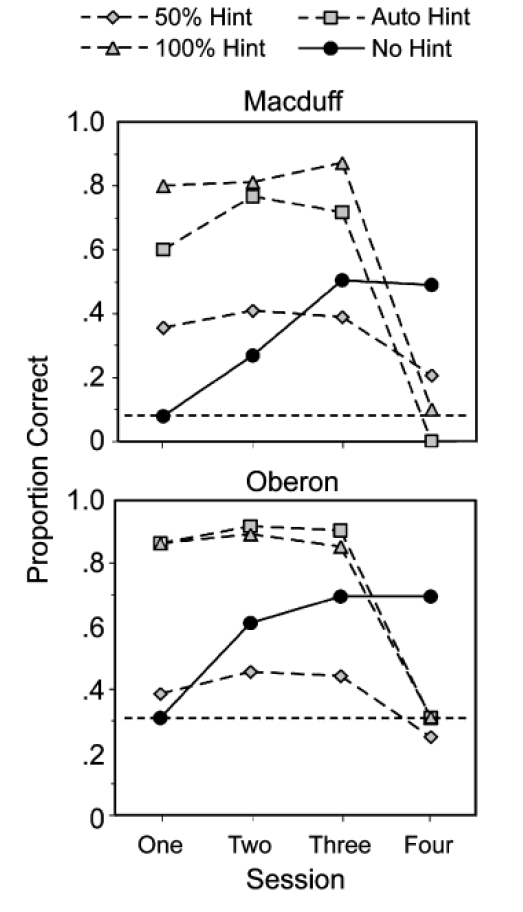

Nate Kornell and Herbert Terrace published a study in 2007. In it, they put two monkeys, Oberon and Macduff, through 4 different memorization tasks. In all 4 conditions, there were 3 learning sessions, and a subsequent test to see the effectiveness of those learning sessions. The four conditions were as follows:

-

Hints were automatically provided during the training sessions

-

Subjects could obtain a hint during training whenever they liked by touching a “hint” button.

-

Subjects could obtain a hint on 50% of training sessions. In the other 50%, no hint was available.

-

No hints were available.

Check out the image below to see the results.

Only the condition in which no hints were provided saw consistent increases in performance through training and an overall increase in performance on test day (day 4).

When learning a sequence by trial and error, it is necessary to make some errors to learn which responses are not appropriate at different steps of the sequence. The need to make ‘‘logical’’ errors (2) during the acquisition of a simultaneous chain provides an important clue as to why hints were not effective under any of the hint conditions in this experiment (3).

Struggle and mess were not only rewarded in the case of this study, but they were necessary in order to see learning benefits.

Notice, in sessions with 100% hints or automatic hints, we saw nearly “perfect practices.” The monkeys were thriving in practice! Success rates were at or above ~80%, as compared to the no hint condition, where their practice sessions were ugly – never reaching ~60% success rates – gross.

But who thrived on gameday? Who balled out on test day? The messy practice condition. The condition that elicited struggle.

The ex-accountant in me wants those clean practices. They are satisfying and confidence boosting… but are they benefiting the athlete?

Let’s dive a little deeper into this learning phenomenon…

The Generation Effect

The generation effect is the experimental finding that when a subject is asked to generate all or part of a stimulus item, that item is almost always remembered better than material the subject only read (1).

When we are forced to generate our own answers, we remember them better, and further, we learn more effectively. Working to generate answers elicits a higher degree of thought (and potential struggle), which creates a usable knowledge as opposed to being given the answer.

A 2007 meta-analysis concluded the following:

These analyses indicate that the generation effect is a robust and consistent finding. Calculations made with 17,711 subjects revealed that there was almost a one-half standard deviation advantage (.40) in memory performance when material was generated versus when it was just read (1).

Can this be applied to sports performance?

Is there a difference between telling an athlete how to move vs. allowing them to discover it for themselves? Will one be more retainable? Will one provide usable movement solutions in the future?

The generation effect tells us that by allowing the student (athlete) to generate their own solution (movement), and potentially struggling and failing in doing so, there may be greater learning taking place than if the teacher (coach) were to simply tell the student (athlete) the solution (movement).

Would you rather have one fish or know how to fish?

Would you rather have one move to beat your defender, or have the ability to formulate new ones?

One 2005 study looked at tennis players, comparing various coaching styles and the subsequent reaction and anticipation times in athletes.

They placed the subjects into 4 groups:

-

Explicit Instruction – In this group, the athletes were told directly how to move, what to look for, etc.

-

Guided Discovery – Think of this more as the middle ground between the explicit instruction group (above) and the discovery group (below).

-

Discovery – In this group, the athletes were directed minimally and allowed to self-organize and learn through their own actions, results, and practice.

-

Control group that did not practice at all.

What they found is very interesting… Conditions 1 and 2 improved at the most rapid rate. Condition 3 improved the slowest. However, when tested under a stressful condition, only groups 2 and 3 showed improvements in performance (4).

This shows us that simply telling an athlete how to move, directing them, without allowing them to think for themselves, may lead to performance decrements under stressful conditions. And, if you think about it, this makes sense…

Athletes need to think for themselves. They need to create their own movement solutions. Both the generation effect as well as this study tell us that the best way may be, get this, less coaching.

But that’s tough to swallow. That is an ego hit. My job as a coach is to not coach? Seems pretty backwards.

In my opinion, my job as a coach is to maximize the value that I provide to my athletes, to subsequently maximize their athletic performance. If this is truly the goal of the coach, we need to understand that sometimes it may be best to stand on the outside and simply observe.

But… Obviously there is a grey area here that needs to be navigated.

Navigating the Grey Area – To coach or not to coach…

Let’s not totally jump overboard. There probably is a thing as too much mess, there is definitely a thing as too much stress, and simply not coaching your athletes, is not the answer. There needs to be a balance here, a middle ground.

As discussed above, we need mess in our training session. It has the potential to boost long term performance and learning. It allows for athlete creativity and it creates a fun training environment.

However, on the other end of the spectrum, we need a degree of cleanliness in our training sessions too. By doing so, we can boost an athlete’s confidence and they’ll leave a training session feeling positive. Cleanliness creates an element of organization and by doing so we maintain a greater degree of efficiency in the training session. And lastly, as shown in the study highlighted above, if rapid learning is the goal, cleanliness and high quantities of coaching is the answer.

Further, we need to look at the population we are training, the goals of the session and the long term goals of the athlete. If we are working with younger athletes (middle school and high school, maybe even young collegiate) a large goal of training may be to develop a foundation of strength. In order to develop this foundation, we need to load the body. In order to load the body safely, we need loaded movement patterns to be within an acceptable threshold, and therefore eliciting the adaptations we are seeking.

I don’t want my middle school athlete to be goblet squatting with extreme levels of lumbar flexion. Or, if posterior chain activation is the goal, I can’t have an athlete squatting his RDLs. Depending on the population, a degree of directing is necessary.

However, let’s flip that coin again…

Even with young athletes, we want to build a robust movement system that is fueled by creativity, exploration and effectiveness. Therefore, to a degree, I want my young athletes to ‘figure it out.’ So often, our youth are told what to do, where to be, how to solve problems. I view the gym as a space that allows them to be the solver. It allows them to be creative. It allows them to showcase their personality through movement. When we are doing 5 yard sprints, I want them to pick the position they start out of. I want them to figure out the fastest way to reach the 5 yard mark. When we are throwing a med ball, I want them to figure out the best way to launch that thing into the air. Even when we are squatting, I would love for them to figure out the most efficient and effective way to squat.

But, there is a limit to everything. There is a middle ground that needs to be established. In this case, how much discovery is too much? At what point do we need to factor in safety? At what point does the athlete need direction in order to solve the problem? On the flip side, how much direction is too much? At what point are we harming creativity? At what point are we not giving the athlete enough freedom?

Finding these answers is the hard part. Navigating the grey area is the hard part. Finding the balance can be messy for coaches.

Wait a minute… mess is stress, which creates growth.

No doubt, the generation effect applies to coaches as well. If we would simply be told where this middle ground lies, we would not grow as coaches. The process of trying to establish it; the process of trying to navigate this grey area; the process is what will help us improve. Understanding that, and viewing the daily balancing act as an opportunity to solve the problem will push us to be better coaches.

Wrap up

In the end, the point is, we as coaches need to find ways to incorporate mess, disorder, and exploration into a training session. Messy has been proven to be a catalyst for learning, memory and growth – I believe we can apply it to our motor learning, problem solving and athletic endeavors. Clean can be boring, and fun does not mean less impactful work.

After all it is very rarely possible to produce perfection of movement every time, so it is logical to programme the nervous system and brain to respond with an effective contingency plan of actions whenever imperfections of movement or accidents occur (7).

Give them space to explore, and you’ll be blown away by the results.

.

.

.

Mess is stress, and it leads to growth.

About Carter Schmitz

I graduated from the University of St. Thomas in 2019 with a business degree and a minor in exercise science. While there, I played football (as long as we consider being a kicker, playing football) and found two of the deepest passions in life - learning and human performance. Since then, I have become a certified strength coach, TPI Specialist and have had the opportunity to train hundreds of athletes ranging from the middle school to the professional level.

I believe in building humans first, athletes second.

I believe that everybody has extraordinarily high amounts of value to offer.

I believe that the pursuit of improvement will lead to growth, no matter the outcomes.

With my writing, I strive to break down and apply complex ideas in order to boost understanding, draw comparisons from seemingly separated and opposing topics, and empower growth in my readers. Knowledge and understanding are power, and they create the foundation of improvement. Moving forward, I plan on continuing to seek the betterment of my athletes, myself and my community, empowering growth along the way.

Be sure to check out my Instagram and YouTube channel for more content:

Instagram - https://www.instagram.com/coach_carter_schmitz/

YouTube - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ7DxYHKGuZIykzVIaxp3XQ

Sources

-

Bertsch, S. et al. “The generation effect: A meta-analytic review.” Memory & Cognition 35 (2007): 201-210.

-

Terrace, H.S., Son, L.K., & Brannon, E.M. (2003). Serial expertise of rhesus macaques. Psychological Science, 14, 66–73.

-

Kornell, Nate & Terrace, Herb. (2007). The Generation Effect in Monkeys. Psychological science. 18. 682-5. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01959.x.

-

Smeeton, Nicholas & Williams, Andrew & Hodges, Nicola & Ward, Paul. (2005). The Relative Effectiveness of Various Instructional Approaches in Developing Anticipation Skill.. Journal of experimental psychology. Applied. 11. 98-110. 10.1037/1076-898X.11.2.98.

-

Taleb, N., 2012. Antifragile.

-

Glasser, William. Choice Theory: a New Psychology of Personal Freedom. HarperPerennial, 2001.

-

Verkhoshansky, Y. V., & Siff, M. C. (2009). Supertraining. Rome, Italy: Verkhoshansky.